Welcome back to the reread of K.J. Parker’s The Folding Knife. You can find the discussion of the previous chapters here.

Last week we swept through all of Basso’s childhood, from the day he was born to his wedding night. This week, Basso makes something of himself. Several things, really—one of which is “murderer.”

Chapter 2: The Monstrous Scope of His Ignorance

For his wedding present, Basso’s father gives him a million shares in the bank. Which sounds like a lot, but we get the impression it isn’t worth that much.

Antigonus, the elderly slave assigned to tutor him, issues Basso a challenge: put up or piss off. Either Basso really needs to learn banking (like Antigonus) or he really needs to get out of the way (like his father). Basso, stunned, chooses to stay.

Antigonus makes Basso work like he’s never worked before in his life. Cilia doesn’t get it. Basso’s making no money and is being abused by a slave. But Basso gets good at his job. After an unspecified period of time (Antigonus generously refers to it as “very short”), Basso graduates from his informal apprenticeship and takes responsibility for the bank.

At some unspecified point over the next two years, Antigonus buys his freedom from Basso’s father and leaves for another bank. But he’s not gone for long, as Basso outfoxes him in a banking duel (alas, not at high noon) and forces him back.

Meanwhile, Cilia gives birth to twins, but we don’t learn their names. His sister Lina also gets married—to a young noble named Palo. They have a son. Basso’s nephew, two years younger than the twins, is named after him. It is all very sweet.

Seven years after the twins’ birth (five after Basso’s nephew’s), Basso completes another enormous banking-related victory. In a fit of giddy triumph, he takes off early to go home and celebrate with this family. Uh oh.

As he comes home, Basso finds Cilia in bed with Palo. Palo attacks Basso with his dagger, stabbing him through the left hand. Basso responds with his own knife (you know, the folding one) and kills him. In a sort of daze, he steps forward and kills Cilia as well. This is the scene from the prelude, of course, but now we have a bit more in the way of names and context. The twins, still unnamed, walk in the gory scene.

Basso calls for the guards. They arrive with our old friend Aelius. He and Basso recognize one another. Due to the intricacies of the Vesani legal system, charges are never pressed and Basso is never called to account for the deaths of his wife and brother-in-law.

Yikes.

I, Basso

As hinted in the prelude: Basso’s no looker. He’s not only described to the reader in unflattering terms but we can see the impact of his appearance on those around him. This included a young Celia, stopping in the aisle at her betrothal. Basso’s apology to her for being “ugly” is heart-rending.

His partial deafness doesn’t help either. He looks “pretty weird” as he has to contort himself to hear people on his bad side, and people treat him like he’s completely deaf, even though he’s not (20).

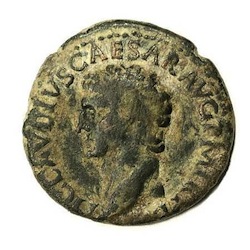

How’s the add up? Basso is physically similar to the Roman Emperor Claudius, who Suetonius describes as:

“afflicted with a variety of obstinate disorders, insomuch that his mind and body being greatly impaired, he was, even after his arrival at years of maturity, never thought sufficiently qualified for any public or private employment” (Alexander Thomas translation, available on Project Gutenberg)

In Robert Graves’s I, Claudius (Cassell: 1934), the narrator (Claudius himself) goes into great detail when it comes to these “impairments”, including being “slightly deaf in one year” (64). Claudius further describes how everyone thought him an “idiot” as a child, including his grandfather, the Emperor Augustus, who “hated dwarves and cripples and deformities, saying that they brought bad luck” (67).

The parallels go further than just Basso’s appearance. Claudius admires Augustus in the same way that Basso admires his own father: from a distance. They’re remote, ambitious figures—and both clearly obsessed with their luck (Augustus was famously superstitious). When Claudius finally succeeds in demonstrating that he’s no fool, Augustus makes more time for him. Augustus never realizes the full extent of Claudius’ gifts, but at least he puts his grandson to good use. Claudius is also assigned a foreign slave as a tutor: Athenodorus.

The most critical similarity of all: Claudius’s wife, Messalina, was famous in both literature and history for her infidelity.

Like Cilia, Messalina was also far more attractive than her husband, and took advantage of his responsibilities as emperor (conquering and lawmaking and such) to cavort. Claudius was devoted to his wife, and, thus both distracted and duped, failed to notice her extracurricular activities. According to Juvenal, these were awfully saucy indeed.

Claudius, like Basso, is responsible for the death of his wife and her lover. Although, as emperor, he didn’t actually hold the knife himself. [This is not a spoiler—it happened two thousand years ago.]

Again, like Basso, Claudius never doubted that he was justified in his actions. For Claudius, Messalina’s death wasn’t just revenge, but a matter of political and cultural necessity. For Basso, Palo’s death was self-defense, and arguably, so was Cilia’s; he believed that she was so “filled with hate… that there was only one thing he could do”.

In Graves’s interpretation—he was ever the poet—Claudius’ life effectively ended at this point. He continued to go through the motions, but was an empty shell of a man, dwelling in the past. Suetonius, to some degree, agrees. He describes Claudius as an increasingly doddering, lackluster emperor, preyed upon by those around him.

This is where Basso and Claudius go their different ways. Basso is also haunted by his actions until the end of his days—we know that from the prelude. But at this point in his life, he’s far from finished.

Or is he?

Other thoughts, at a slightly brisker pace:

Knives! Antigonus has a “silver-handled penknife that nobody else is allowed to use” (42). Palo has a “dress dagger, jeweled-gilded hilt and a bit of old tin for a blade” (56). Basso’s own knife is everywhere—cutting both cake and people. The knives fit the characters, too. Antigonus is elegant but restrained, distinguished but always useful. Palo is gaudy, appealing and, ultimately, blunt and useless. So what does Basso’s knife make him?

We get things in the wrong order again: “Three days before the twins were born, Antigonus came in late” (38). This is a graceful way of reminding us not only that Antigonus is more important to Basso than his children, but also that, ultimately, Basso’s “coming of age” isn’t becoming a father, but becoming a banker.

Simnel cake is apparently a real thing. It sounds kind of gross. But then, I don’t like almonds, fruit cake or marzipan. So who am I to judge? According to Wikipedia, Simnel cake has a long history (in Britain; possibly back to the 13th century!) and is generally part of Easter celebrations—a sort of post-Lent treat. If anyone can draw a connection here, I’m all ears. Perhaps Basso’s days of apprenticeship are like Jesus’ days of fasting? With the Devil tempting him to give up, a bit like Cilia does? Does this mean Antigonus is a British analogue? When is a fruitcake just a fruitcake? (Probably now.)

It seems that Basso has very quickly distanced himself from his father. He’s taken Antigonus’ position to heart, namely, that his father’s “only commercially valuable quality is his luck.” In this chapter, Basso is keeping his dad out of the loop. He hides how much the bank is worth, for example, and what risks that he, Basso, is taking with their money. At the same time, he’s disappointed when his father doesn’t figure it out. Poor guy.

The above could be one of the reasons that Basso goes to such great lengths to buy back Antigonus—there’s literally no one else capable of appreciating his genius. Did Basso really crush one of the largest banks in the Republic and risk his own family’s fortune just to get Antigonus back? Or to get back at Antigonus? (As in last week’s discussion of the stolen coat—I’m pretty sure the one thing it wasn’t about was the money!)

The Gazetteer

With each chapter, I’m going to pull out the world-building stuff and tack it here, at the end of the post. If you spot references to these things in other KJ Parker books or stories, please say so in the comments!

- Jazygite—of a particular race or, perhaps, nation—a person from Jazia? (Jazygia?)

- Metanni—also referring to a people of another race or nation—(Metannus?)

- Strait of Neanousa—geographic feature

- Ousa—another country

- Euoptic—another country (possibly region and/or body of water)

- Soter Peninsula—geographic feature, also Soter City

- Simisca—another city, not far away

- The Horn—a region (sounds a bit coastal, right?), also not far away

- Ennea—a place (probably a city)

- General Tzimiscus—foreign mercenary, “chopped to pieces”

- The Invincible Sun—the religion; this definitely pops up over and over again

- The naming convention of the banks (“Charity and Social Justice”) is similar to that of the inns and roadhouses in the Scavenger trilogy. Not sure if there’s a connection between them.

Well, Basso’s now a father, a banker and a murderer. How will he top this? By going into politics?!

Jared Shurin likes K.J. Parker a lot.